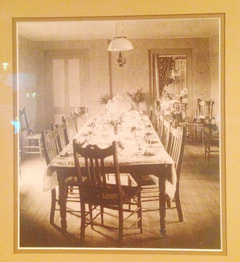

A rare, first-hand account of a trip inside the city's hidden bomb shelter is the second part of this series. In 2006, with the promise of its location remaining a secret, writer Bill Sievert and photographer Rich Stayton were given permission to go underground for "Gimme Shelter", an article published in PULSE Magazine and now republished by Mount Dora Buzz. (For Part 1, click here )  A TRIP DOWN UNDER As Richard and I inch our way into the eerie darkness, having nothing but a flashlight and Richard’s flashbulbs to illuminate our path, I am overcome with the feeling that a nuclear holocaust truly has occurred and that we are witnesses to the end of civilization. Just past the steel trap door, the first relic we notice is an old-fashioned drug-store-style scale, which creates a momentary illusion that we are entering an amusement park funhouse (the dark and scary kind). We imagine that the scale was placed there not for member weigh-ins, but as a good-humored attempt to lighten the mood of panicky arriving occupants. Even the official house rules, a copy of which was provided to Pulse by the owner, are frightening. The regulations placed “authority for maintaining order” and “enforcement” of all rules in the hands of the Security Committee. “Distribution of all food and other supplies in storage will be in the hands of the Security Committee. … All firearms brought into the shelter will be tagged and locked up by the Security Committee ... The Security Committee will stop all disputes between parties, and those of a serious enough nature will be arbitrated by an arbitration committee composed of the chairmen of the Security, Medical and Maintenance Committees and two members of the Board of Directors. … The Security Committee may select from among the able bodied men additional persons to aid in protection of the shelter.”  The Medical Committee, led by Dr. Hall, was assigned responsibility for the “health and welfare of the shelter… All minor illnesses will be treated at a Sick Call at 8 a.m. each morning. Serious illnesses will be treated at any time.” Smoking, not regarded the health hazard it is known to be today, was permitted, but only in the 40-foot by 20-foot great hall. Other rules instituted curfews: “Children under the age of 9 years must be in their units by 7:30. All persons must be in their units by 11 p.m. and quiet time will be observed until 7 a.m. There will be a quiet hour from 2 p.m. until 4 p.m. daily.” It was left unstated how the Security Committee intended to punish infractions of policies when, as time wore on, children misbehaved and adult tempers flared. An “Agricultural Committee” was to “make assignments of jobs to the members for the purpose of growing crops to feed the members after leaving the shelter.” The committee had a lot to work with. On our tour, we are amazed at the stockpile in the large closet known as the “seed room.” The metal shelving units on which the cans once stood have crumbled into rusty red dust, but hundreds of containers of seeds, most of them still sealed and secure from the prowling roaches, have spilled into the hallway.  The seed room is located at the northern end of one of twin corridors that attach to the central hall on both sides, forming a layout shaped like the letter H. The hall, which served as the communal recreation and meeting room, is situated just beyond a thick wooden door from the entrance area (the wood door served as a secondary barrier to access, just in case someone successfully circumvented the steel trap). The wood door also kept residents away from the electrical-generator room (the shelter had a sophisticated system of air-conditioning and air filtration) and a decontamination room. In one corner of the common hall is the community kitchen, its four-burner stove and sink still present but the latter crumbling badly. There’s no way, we think, that such a tiny facility, seemingly designed for a cottage or motel room, could possibly handle food preparation for up to 100 people. The rules said nothing about cooking or dining shifts, so we have no idea how the residents planned to share the space.  Some people, however, must have been planning to dress for dinner. In one of the sleeping units in the west wing of the H, we are startled by the form of a woman – but, resisting the urge to run, we discover that it is merely a ragged, patterned party gown draped over an old wire hanger. At one time, the dress had been beautiful and probably quite expensive; now it was the last remaining garment on what had been a rod full of clothing. Perhaps it belonged to the wife of the coop member who, according to the current owner, left behind an entire rack of business suits. Some of these people clearly intended to maintain a semblance of formality. Most of the shelter’s contents were cleared out before the cooperative dissolved, and other items were removed by the property’s current owner. Still, what remains constitutes a memorable peek into what it might have been like to inhabit The Catacombs. I won’t easily forget a child’s playroom or, perhaps it was intended as a classroom. In one corner, a handcrafted dollhouse leans atilt against a rickety plank bookcase. On a shelf is a short stack of decayed volumes – no titles could be deciphered – but from the index thumb markers, the top book appears to be a dictionary. Nearby, pieces of an abandoned jigsaw puzzle – its once bright imagery reduced to plain cardboard – have melted into a tabletop.  Searching gingerly through the relics of The Catacombs is not unlike sorting through the pieces to a complicated jigsaw puzzle – one bit of history fits here, another there. Richard and I stay much longer than we had planned, despite my expressed fear that the owner (who had left us alone) might become annoyed at our dawdling and seal us inside. Even in such a large space, it is impossible to escape the feeling of claustrophobic confinement. As we finally begin climbing the stairs and notice rays of sunlight pouring in from above, I can’t help but wonder whether something should be done to preserve what is left of this one-of-a-kind monument to a dark period of history, and to restore what has been lost. Perhaps a state or federal agency should attempt to purchase the property, turn the lights and air-conditioning back on, and allow the public inside. Our planet still possesses the capability to destroy itself with nuclear weaponry many times over, but if enough people had access, The Catacombs could serve as a strong reminder why we never want to come so close to the atomic precipice again. If you missed the Part 1, click here. For part 3, click here. "Gimme Shelter" was written by Bill Sievert, owner of The Wow Factory in downtown Mount Dora, and Richard Stayton was the photographer. Bill was one of the founding partners of PULSE, along with Carole Warshaw, Jane Trimble and Aaron Marable. Permission was generously granted to Mount Dora Buzz to reprint the story, so more people could learn of this piece of local history.  The community's shrouded atomic bomb shelter is arguably the most intriguing aspect of Mount Dora's past, yet many residents know nothing about it. Mount Dora Buzz was generously given permission to reprint Bill Sievert's captivating article. "Gimme Shelter", that uncovered the city's secret catacombs, reportedly the largest private bomb shelter in the country. GIMME SHELTER PART 1 of a 3-Part series They all knew what they’d have to do. At the very first wail of an air-raid siren or the earliest broadcast bulletin of an impending atomic attack, they were ready to drop everything and rush to the secluded refuge they had created six feet under an orange grove on the edge of Mount Dora. As many as 100 members of 25 prominent local families – doctors, lawyers, a bank president, a minister and even Mount Dora’s mayor – would strive to reach their shelter in time. For, once the “Security Committee” had dropped the steel trapdoor across the entranceway, any stragglers (including spouses and children) would be left behind. And all those who made it down the concrete stairwell into the bowels of the 5,000-square-foot labyrinth knew that it would be impossible for them to open that2,000-pound door again. Rather, after enduring their elaborately organized underground domain for as long as six months, the survivors of nuclear warfare would have to dig their way out through a partially pre-constructed tunnel or “escape hatch,” carrying with them cans of uncontaminated seeds they had safeguarded during their time below. Built secretively at the height of nuclear tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States in 1961, “The Catacombs” was not only the biggest privately constructed shelter in our area, but federal officials have termed it the nation’s largest. Yet, its affluent members were far from the only residents of our towns to jump on the bomb-protection bandwagon. Homes all over the area – from Deidrich Street in Eustis to Alfred Street in Tavares to Tremain Street and Tenth Avenue in Mount Dora – still boast fallout shelters, all dug by fearful folks in the late 1950s and early 60s. Today, most of the concrete rooms are used for storage, though several owners see their potential as hurricane hideouts, wine cellars or party rooms.  Were people in our communities unusually preoccupied with the possibility of a nuclear attack? In a sense, they were. While the entire nation was gripped by fright and students everywhere practiced “duck-and-cover” drills beneath their school desks, Floridians felt especially vulnerable because of our proximity to Soviet missile sites in Cuba. However, residents along the coasts and in South Florida were too close to sea level to dig underground asylums. In this area we had plenty of high-and-dry spots to make the temptation practical. “I was in high school in Lauderdale and whenever we visited my grandparents in Mount Dora, they would take us down for a look at their shelter,” recalls Ruth Ault, who now lives here. “My dad made us watch John Kennedy’s famous TV speech [during the Cuban Missile Crisis of October, 1962], and it put a scare in me. It bothered me that we couldn’t have a place to escape in South Florida like my grandfather did.” In the tri-towns of Mount Dora, Eustis and Tavares, the fear became particularly palpable after the publication in 1959 of writer Pat Frank’s nationally renowned novel “Alas, Babylon.” It is the story of one small Florida community’s struggle for survival following the nuclear annihilation of Miami, Tampa and Orlando. Frank, actually the pen name of journalist Harry Hart, lived in Mount Dora at the time he wrote the book, and his fictional setting of Fort Repose was (not coincidentally) one of a triangle of small towns not too far north of Orlando.  Locals immediately linked the novel’s locale to Mount Dora, Eustis and Tavares, and began to identify with the characters and the chaos they faced. In the story, all power and communication with the rest of the country is lost, the local doctor is beaten up by drug addicts, the police chief is murdered and the bank president, unable to cope, kills himself. Not long after “Alas, Babylon” became a best-seller, Lake County Health Director Dr. James Hall, citrus magnate William Baker, and retired paper-manufacturer and big-game hunter Theodore Mittendorf, as well as several of his fellow members of The Mount Dora Yacht Club, approached local builder J. G. Ray about the idea of designing a group shelter for their families. They thought that pooling their efforts would be more cost-effective than creating single-family shelters, and that they would draw comfort and strength from their number. Ray took on the $60,000 job, even though he personally did not care to join the cooperative venture, which cost each participating family at least $2,000 toward construction plus around $200 in annual upkeep fees. According to his son, Jeff Ray III, who was in college at the time, “My dad was offered a room in the building as part of his fee. He told me that he said to them, ‘No way! I’m not about to go in there with a bunch of old fogies.”  The senior Ray, who was in his 40s at the time, also confided to his son that he declined to accept a share because, with his children away at school, it was unlikely he could gather his family in time to use it. Jeff Ray did have the opportunity to tour the facility during its period of peak preparedness. He especially recalls the “arsenal of weapons [which included numerous .357 Magnums and about 10,000 rounds of ammunition] and the places where bodies would be stored.” The project was so carefully thought out that even the likelihood of resident deaths was anticipated. Burial crypts line the wall at the base of the entry stairs, across from the electrical-generator room. More than 30 other rooms are included in the complex, including 25 family residences, each 12-foot by 12-foot (about the size of a small college dorm room). There is a kitchen at the edge of the central hall for group gatherings, separate lavatories for men and women, and a medical clinic, which is still furnished with a refrigerator for chilling antibiotics and a reclining wicker wheelchair where one of several doctors could perform examinations or even surgeries.  Fortunately, the coop members never had to avail themselves of such services. As a group, they spent only one night living inside the shelter for a drill. Still, they stocked the kitchen, the seed pantries, the pharmacy and their individual rooms with everything they thought they would need, from party gowns to children’s toys (one family even horded chocolate bars), in hopes of living with some pretense of normalcy. They were fairly successful in keeping the project secret from the local public, who they feared would demand access in an actual emergency. Maintaining confidentiality was no easy feat, particularly with lots of heavy equipment and a large crew on site during six months of construction. According to various reports, the man who offered his property for the shelter told anyone who asked that he was simply building tennis courts or (even less credible) a croquet court. Today, 45 years after its construction, The Catacombs remains remarkably intact, though the foot-thick walls teem with thousands of palmetto roaches, and rust and mildew are abundant, having flourished since the electrical system and dehumidifiers were disconnected many years ago. The original cooperative relinquished its claim to shares of the underground space in the 1970s, long before the current owner purchased the property two decades ago. The owner recently permitted Pulse photographer Richard Stayton and me to tour the complex. (We agreed not to divulge its location due to concerns about liability as well as his privacy.) The entrance is in a shed just beyond the backdoor to his home, which was built soon after completion of The Catacombs. Taking deed to the giant shelter was not a consideration in his family’s decision to purchase the property. “I couldn’t figure out anything legal to do with it,” he says with a laugh. “Hydroponic gardening, perhaps? Initially, there were some parties, and my kids played in it a few times. But eventually I just closed it up.” “What is mind boggling to me,” he adds as we descend the stairwell into the darkness, “is that so many people could come together to do this thing.” Click here for Part 2 when the writer and photographer take a trip inside the catacombs. "Gimme Shelter" was written by Bill Sievert, owner of The Wow Factory in downtown Mount Dora. The photographer was Richard Stayton. The article was originally published in PULSE Magazine in 2006. Bill was one of the founding partners of PULSE, along with Carole Warshaw, Jane Trimble and Aaron Marable. There are catacomb photos included in this re-published article that have never been published. The top photo is the staged PULSE cover photo of the issue featuring local residents Michele & Ric Wilson and their children in a much smaller bomb shelter. For more local news click here... |

Archives

February 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed